In the empirical inertial Phillips curve I use today, price inflation does not depend on wage inflation, but rather the unemployment rate gap, lagged inflation, and inflation expectations. And this is what I see as the conventional specification of the Phillips curve today. However, that’s a dramatic break from how I thought about inflation dynamics a long time ago. Then, the model of inflation dynamics began with a wage Phillips curve that then drove price inflation via a markup equation.

Let’s explore inflation dynamics today and the prospect that a wage-price spiral will make higher inflation more persistent and leave inflation above 2% (or raise it further above 2%) over the forecast horizon.

Demand-Supply Imbalances in Output and Labor Markets

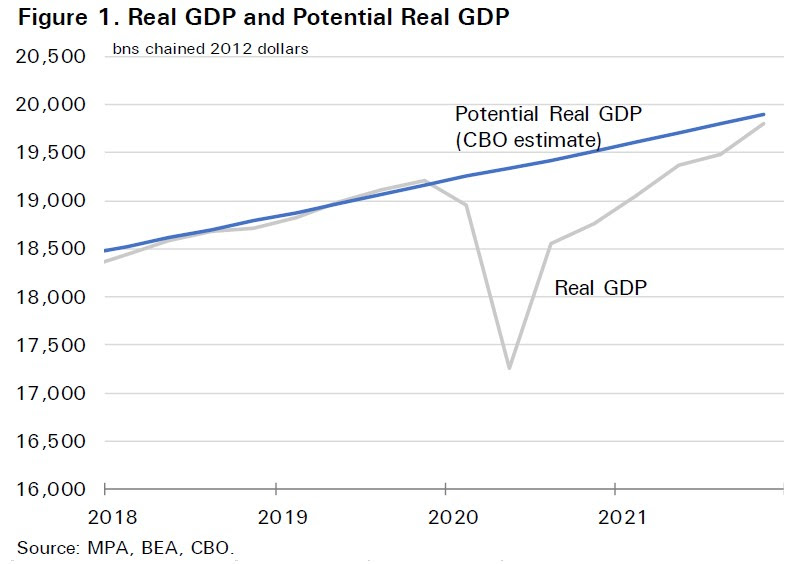

One reason for believing wage inflation may have an elevated role as a determinant of price inflation is that the supply-demand imbalances may be very different today in the two markets. I expect this is because of the unique effect of the pandemic on the labor market, as reflected in the participation rate and, especially, the historically high quits rate.

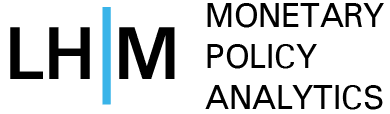

An important caveat: The aggregate price pressure in 2021 was initially the result of very sharp price level shocks due to supply chain disruptions in Asia. These broadened, especially to a range of imported durable goods, via the transportation and logistics disruptions and via the sharp rise in oil prices. Now higher prices seem to be almost everywhere—though the largest increases are still mainly in goods. But this, I contend, is different from periods when higher price inflation reflected a rise in actual output above potential. Perhaps too fine a point, but I think it’s important in this context.

To read more, send us a message.